12) Extra-Biblical Literature - Part 2: A Brief Overview of Extra-Biblical Sources

The Apocrypha

The Apocrypha refers to a collection of ancient texts of uncertain or disputed authenticity and, therefore, are not included in the canonical Scriptures of some religious traditions. These texts are often included in some versions of the Bible but not in others. The Apocrypha contains books that were written during the intertestamental period (the time between the Old and New Testaments) and includes works such as Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, and additional portions of Daniel and Esther. Different religious traditions have varied opinions on the status and inclusion of these texts in the biblical canon. The study and understanding of the Apocrypha contribute to a more comprehensive view of the biblical and historical context in which these texts emerged.

The Book of Tobit

The Book of Tobit, also known simply as Tobit, is one of the books of the Apocrypha. The book is presented as the memoirs of Tobit, a righteous Israelite of the tribe of Naphtali. The authorship is traditionally ascribed to Tobit's son, Tobias. The composition is typically dated to the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE. Tobit is a narrative work that combines elements of historical fiction and religious didacticism. It incorporates themes of piety, morality, and divine intervention. The story is set in the Assyrian period, reflecting the historical context of the Assyrian exile of the northern tribes of Israel. Tobit's narrative unfolds with themes of faithfulness to God amid trials. Tobit's piety leads to misfortunes, including blindness.

Meanwhile, Sarah faces a series of tragic events, including the death of her seven husbands. Disguised as a human, Raphael guides Tobias on a journey to retrieve money from a distant relative and ultimately assists Sarah. Throughout the story, divine intervention and angelic guidance are evident. The Book of Tobit is valued for its moral and theological teachings, presenting a narrative that reflects on the complexities of human life and the role of faith in navigating challenges.

The Book of Judith

The Book of Judith is another work found in the Apocrypha. The book is presented as a historical narrative but is considered fiction. The authorship and dating of Judith are uncertain, with most scholars placing it in the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE. The story is set during the Babylonian exile, specifically during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II. It centers around the Assyrian siege of the Jewish city of Bethulia. Judith tells the story of a courageous Jewish widow, Judith, who uses her beauty and wit to infiltrate the enemy camp during a siege. She gains the trust of Holofernes, the Assyrian general. She ultimately beheads him, delivering a decisive blow to the Assyrian forces. The victory boosts the morale of the Israelites and leads to the salvation of Bethulia. The Book of Judith is celebrated for its dramatic storytelling and portrayal of a strong female protagonist whose actions contribute to the deliverance of her people. It is read and appreciated for its moral and theological insights, though its historical accuracy is debated.

The Wisdom of Solomon

The Wisdom of Solomon is a deuterocanonical book found in some versions of the Old Testament, particularly within the Apocrypha. Traditionally attributed to King Solomon, the son of David, though scholars generally consider it to be pseudonymous. The book is believed to have been composed in the 1st century BCE, likely in Alexandria, Egypt. The Wisdom of Solomon is a philosophical and didactic work that falls within the genre of wisdom literature. It is characterized by its eloquent and rhetorical style, drawing on Hellenistic philosophical traditions. The book addresses the Hellenistic Jewish community and seeks to encourage fidelity to Judaism while engaging with Greek philosophical thought. Themes include the pursuit of wisdom, the nature of righteousness, divine justice, and the soul's immortality. It explores the contrast between the righteous and the wicked.

The book begins with exhortations to pursue wisdom and extols the virtues of righteousness and faithfulness. The middle section presents a theological reflection on the fate of the righteous and the wicked, emphasizing divine justice. The concluding part praises the wisdom of God and the benefits of possessing divine wisdom. Wisdom is personified as a female figure, and the book attributes various characteristics and actions to wisdom. This personification draws on the wisdom tradition of Proverbs and other biblical books. The Wisdom of Solomon is valued for its insights into the pursuit of wisdom, the nature of righteousness, and the theological reflections on divine justice. It represents an essential development in the interplay between Jewish and Hellenistic thought during the Second Temple period.

Sirach (Ben Sira)

Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), also known as Ben Sira, is a work of wisdom literature attributed to a Jewish sage named Jesus ben Sirach, who lived in Jerusalem in the early 2nd century BCE. The author was well-versed in Jewish tradition and wisdom. Ben Sira belongs to the genre of wisdom literature, offering practical advice on various aspects of life, ethical teachings, and reflections on the nature of God. The book consists of moral teachings, maxims, hymns of praise, and reflections on various topics, including family, friendship, wealth, and the fear of God. It often provides guidance on virtuous living. Initially composed in Hebrew, the text has survived entirely in a Greek translation. Fragments of the Hebrew version were discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Book of Baruch

The Book of Baruch is a deuterocanonical book found in some versions of the Old Testament, specifically within the Apocrypha. Traditionally ascribed to Baruch, who was a scribe and disciple of the prophet Jeremiah. The book is presented as a letter Baruch wrote to the exiled Jews in Babylon. The book's composition generally dates to the Babylonian exile around the 6th century BCE. The book begins with an introduction that sets the context. It claims to be a letter sent by Baruch from Babylon to the exiled Jews in Babylon. A significant portion of the book consists of a confession of sins, acknowledging the transgressions of the people of Israel. The book includes a poetic section called the "Hymn of Baruch," which praises divine wisdom. Baruch encourages the people, urging them to seek wisdom and follow God's commandments. It also contains prophecies about the eventual restoration of Jerusalem. The Book of Baruch provides insights into the religious and theological concerns of the Jewish community during the period of the Babylonian exile. It addresses repentance, wisdom, and the eventual hope for restoration.

Daniel and Esther

Daniel and Esther are two books that are generally not considered part of the Apocrypha. Some versions of the Christian Old Testament, especially those influenced by the Septuagint (Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures), include additional stories or passages in the book of Daniel that are not present in the Masoretic Text (Hebrew version). These extra sections, often called the "Additions to Daniel," are sometimes considered part of the Apocrypha in certain Christian traditions. Like Daniel, Esther also has additional sections in some versions of the Christian Old Testament. The additions to Esther include extra verses and prayers not found in the Hebrew Masoretic Text.

The Book of Maccabees

The Books of the Maccabees are historical and deuterocanonical books that account for events during the Hellenistic and early Hasmonean periods in Jewish history. These books are considered part of the Apocrypha. Four books are commonly referred to as the Books of the Maccabees. The books provide a crucial historical record of the Maccabean Revolt, a pivotal moment in Jewish history when a small group of Jewish rebels successfully resisted the religious oppression of the Seleucid Empire. The events of the Maccabean Revolt, particularly the rededication of the Second Temple, are associated with the Jewish festival of Hanukkah. They offer valuable insights into the challenges faced by the Jewish community in the Hellenistic period and their commitment to preserving their religious identity.

The Pseudepigrapha

The Pseudepigrapha refers to a collection of ancient Jewish and early Christian writings falsely attributed to biblical figures or other notable persons. The Pseudepigrapha includes writings attributed to figures from the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the intertestamental period. For example, books are falsely ascribed to Enoch, Moses, Solomon, Ezra, and others. The term "pseudepigrapha" means "false writings." These texts were composed during the same general period as the Old and New Testaments. Still, they were not included in the canonical Scriptures.

The Pseudepigrapha includes diverse literary genres, such as apocalyptic literature, wisdom literature, and historical narratives. Examples of Pseudepigraphal works include the Book of Enoch, the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Assumption of Moses, and the Apocalypse of Abraham.

These writings are considered non-canonical and are not accepted as authoritative by mainstream Jewish or Christian traditions. While some of these texts may provide historical and cultural insights into the times they were written, they are not considered part of the inspired Scriptures. Different branches of Christianity and Judaism may have varying perspectives on the significance of these writings. While the motivations behind their composition might not always be clear, these writings offer valuable insights into the diversity of religious thought during the intertestamental period.

The Book of Enoch

The Book of Enoch, also known as 1 Enoch, is a collection of ancient Jewish apocalyptic texts that ascribe themselves to Enoch, the great-grandfather of Noah. The book is traditionally attributed to Enoch, mentioned in the biblical genealogies in the Book of Genesis. The contents of the Book of Enoch are diverse and cover a range of themes, including cosmology, angelology, eschatology, and moral teachings. The Book of Enoch is a fascinating collection of texts that provides insights into the apocalyptic and mystical thought of the Second Temple period. Its rich imagery and themes have intrigued scholars and readers for centuries.

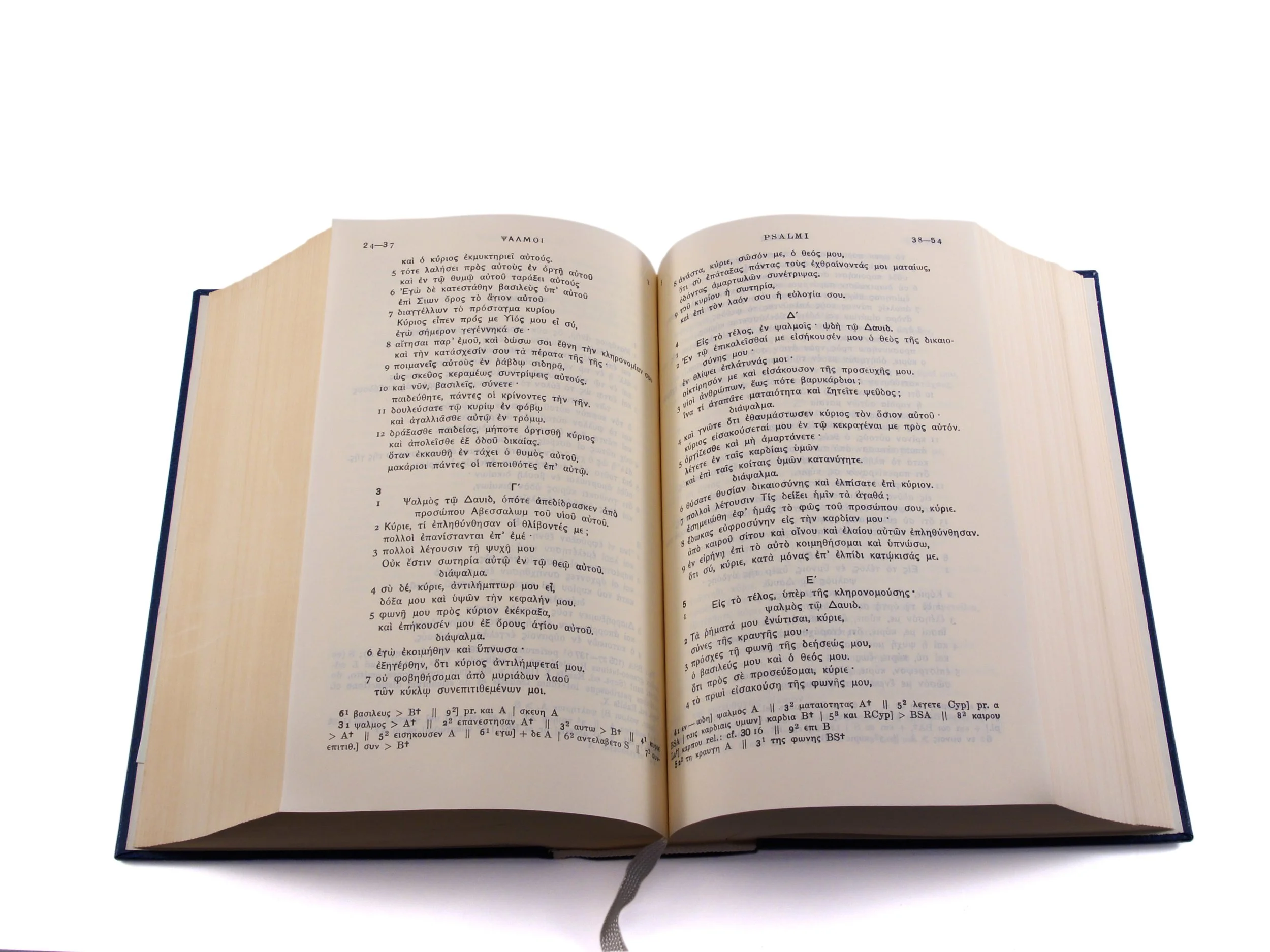

The Septuagint

The Hebrew scriptures, also known as the Tanakh or the Old Testament, were originally written in Hebrew. Most Old Testament texts, including historical books, poetry, prophecy, and law, were composed in Hebrew. Some portions, particularly in the later books of Daniel and Ezra, include sections written in Aramaic, a related Semitic language. However, the predominant language of the Hebrew Scriptures is Hebrew, reflecting the linguistic and cultural context of the ancient Israelites.

The first translation of the Hebrew Scriptures is the Greek Septuagint (LXX), which, according to legend, was translated in Alexandria at the behest of King Ptolemy 11 around 250 BCE. LXX is the Roman numeral for 70, which refers to the Septuagint. According to tradition, the Septuagint was translated by 70 or 72 Jewish scholars. The term "Septuagint" itself means "seventy" in Latin, reflecting the tradition of the 70 (or 72) translators who worked on the translation.

A Greek Old Testament

The Septuagint played a significant role in spreading the Hebrew Scriptures in the Hellenistic world. The term "Hellenistic world" refers to the historical period and cultural influence associated with the spread of the Greek language, culture, and ideas following the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE. The Septuagint became an important version of the Old Testament for Greek-speaking Jews and early followers of Jesus. The Septuagint provides a crucial source for gospel studies because it gives us a perspective on how the Hebrew text was understood by a Jewish community in the post-exilic, Hellenistic world.

By comparing the Greek New Testament Scriptures with the Septuagint, we have a better idea of the original Hebrew or Semitisms that lie behind the Greek text. The Septuagint was the Bible of Hellenistic Judaism and the Diaspora (the Jewish Diaspora refers to the historical dispersion of Jewish communities beyond the land of Israel); it is often quoted in the New Testament and functioned as the equivalent to a canonical text of the Bible in the apostolic world.

The Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a collection of Jewish texts, including biblical manuscripts and other writings, discovered between 1947 and 1956 near the Dead Sea. The scrolls were found near Qumran, near the Dead Sea, and their preservation in the dry climate has allowed scholars to study and analyze them in detail. These ancient manuscripts are of great historical and religious significance, dating from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE.

The scrolls contain fragments from every Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) book, except the Book of Esther, providing insight into the textual history of the scriptures. Additionally, they include sectarian documents related to a Jewish sect often associated with the Essenes, shedding light on the diverse religious landscape during the Second Temple period.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has contributed significantly to understanding ancient Jewish thought, religious practices, and the transmission of biblical texts.

One of the caves of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Midrash

Midrash refers to a method of interpreting biblical texts within the Jewish tradition. It involves analyzing, expanding, and explaining the biblical verses, providing insights into their meanings and applications. "Midrash" can also refer to specific collections of such interpretations.

Long before the days of Jesus, a vast body of Jewish legend, tradition, and folklore about Bible characters and events was circulating. Many of these legends were passed about in the form of midrash (w). Midrash is Hebrew for "something searched out." It comes from the root word darash, which means "to search." As the sages searched the Scriptures to reconcile contradictions, explain obscure passages, or find deeper meanings and hidden allusions, they incorporated much of the legend and folklore they were familiar with into their hermeneutic explanations. As a result, a significant body of Jewish legend passed on through the vehicle of oral tradition in the midrashim of the sages. The oral transmission process carried the material from generation to generation until it was recorded.

Midrashic literature was recorded over several centuries, and its compilation spans a broad historical timeline. The production of Midrashic works began during the Second Temple period, around the fifth century BCE, and continued into the early medieval and later periods. Much of the midrash and what could be termed the "midrashic method" finds its way into the teachings of Jesus and the apostles, far more than one would suspect.

The Targums

The Targums are Aramaic translations or paraphrases of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), mainly focusing on the books of the Torah (the first five books) and other biblical writings. The term "Targum" means "translation" or "interpretation" in Aramaic. After the Babylonian captivity, Aramaic became the common tongue of Judea and Galilee. Hebrew began to fall into disuse outside of religious dissertation. Many of the common people no longer could comprehend Hebrew. Synagogues began using translators to render the Hebrew Bible readings into Aramaic paraphrases, eventually bringing about the writing of Targums.

These translations were developed to make the Hebrew Scriptures accessible to Jewish communities that primarily spoke Aramaic. The Targums provide insights into the linguistic, cultural, and religious context of the Jewish communities that used them. They also offer valuable information about how specific passages were understood and interpreted within Jewish tradition.

The Targums, however, are not literal translations of the Hebrew. Their paraphrases tended to be even looser and more expansive than the popular paraphrases of our own day, such as The Living Bible or The Message. The Targum paraphrases give us a generous amount of traditional Jewish thought regarding interpreting any given text and offer us critical keys to unlocking mysticism in the Apostolic Writings.

Other Influences on First-Century Jewish Thought

During the time of Jesus, the Pharisees and the Sadducees were two prominent Jewish sects, each with distinct beliefs, practices, and roles in the socio-religious landscape of Second Temple Judaism. Both groups were part of the broader Jewish community but had different theological and political perspectives.

The Pharisees were influential in local communities, emphasizing Torah observance and oral traditions. The Pharisees passed on the oral traditions and insisted on the reliability of the fathers' traditions. They believed in the resurrection of the dead, angels, and the existence of an afterlife. The Pharisees were influential among the ordinary people and often held leadership positions in local synagogues. They were seen as experts in interpreting and applying Jewish law. While Jesus disagreed with some Pharisees, not all were portrayed negatively in the Gospels. Some Pharisees were sympathetic to Jesus; a few even became his followers. The tensions with Jesus often revolved around differing interpretations of the Sabbath and purity laws.

We will explore the Pharisees more in future lessons. Still, you should know that it was common for Jews in the first century to have diverse opinions and disagreements on religious, legal, and social matters. Jewish society during the Second Temple period, including the first century, was characterized by various religious sects, schools of thought, and interpretative traditions. Some prominent groups included the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and Zealots, each with distinct beliefs and practices.

The Sadducees were associated with the priestly class, focused on Temple activities, and had more direct connections to political authorities. The Sadducees rejected the oral traditions and their authority and insisted only on a literal reading of the Torah. Unlike the Pharisees, the Sadducees did not believe in the resurrection, angels, or an afterlife. The Sadducees were closely connected to the Temple in Jerusalem and held critical administrative roles. They were involved in priestly duties, including sacrifices and rituals. The Gospels portray the Sadducees as less directly involved with Jesus than the Pharisees. The Sadducees were generally more aligned with the Roman authorities, contributing to their tensions with Jesus, who challenged religious and political structures.

In the days of Jesus, the Pharisees split into two main camps: the disciples of the teacher Hillel and the disciples of the teacher Shammai. The enormously influential teacher Hillel sought to bring leniency to interpreting the Torah. He was known for his humility and his wisdom. His teachings seem to have had a heavy influence on Jesus' own teachings. On the other hand, the far-less-friendly, but no-less-pious, teacher Shammai, best known for his strict, no-nonsense, black-and-white sensibilities opposed Hillel's opinions at almost every turn. Neither Hillel nor Shammai left us a single scrap of their teaching in a written form. However, their opinions, anecdotes, and interpretations fill pages and pages of the Mishnah and Talmud, written hundreds of years later--another testimony to the strength of the oral transmission process.

The disciples of Hillel (Beit Hillel or School of Hillel) and Shammai (likewise) were the very Pharisees Jesus commonly encountered. Hillel's grandson, Gamliel, is the same Gamliel under whom Paul studied. We call this generation of sages the Tanna'im (Teachers). Traditions about these characters, preserved in later texts, record their interactions with the apostolic community and early Christians. They provide essential glimpses into that lost era.

Jesus, Paul, and the disciples are all Tanna'im (teachers). The disciples of Jesus, like the other Tanna'im of their day, were responsible for transmitting the teaching of their Master to the next generation. Matthew, one of Jesus' disciples, wrote a collection of Jesus' sayings in a Hebrew version of the Gospel of Matthew. This Hebrew Matthew is probably one of the sources employed by our three Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke).

The Hebrew Matthew

George Howard discovered and studied the Hebrew Matthew in 1987. He thought it was a translation from Greek. Howard came to the conclusion that it is a Hebrew original. He based his book "Hebrew Gospel of Matthew" on 9 manuscripts.

Epiphanius of Salamis (born around AD 310 and died in 404), spoke on the Hebrew Matthew in his work called "Panarion" (also known as "Adversus Haereses" or "Against Heresies"). The Panarion is a work in which Epiphanius addresses various heresies and presents orthodox Christian doctrine. Originally written in Greek, here is an English translation of the relevant passage from Panarion 30.3.7-8:

"Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter. Luke also, the companion of Paul, recorded in a book the Gospel preached by him. Afterwards, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia."

Jerome, in 392, spoke on the Hebrew Matthew. Jerome was a church father who translated the Bible from Hebrew into Latin, the Latin Vulgate. In his preface to his Latin translation of Matthew's Gospel, Jerome acknowledges the tradition that Matthew originally wrote his Gospel in Hebrew. However, Jerome did not translate directly from the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew; he worked mainly from the Greek manuscripts available. Jerome's comments on the Hebrew Gospel of Matthew are found in his "Preface to the Gospel of Matthew." Here is a brief excerpt:

"Matthew, also called Levi, apostle and aforetimes publican, composed a gospel of Christ at first published in Judea in Hebrew for the sake of those of the circumcision who believed, but this was afterwards translated into Greek though by what author is uncertain."

After the time of Jerome, Hebrew Matthew disappeared for about 1000 years and reappeared in Spain. In the year 1380, Shem Tov Ibn Shaprut publishes a Hebrew Matthew. Where did he get it from? Howard assumed Shim Tov got it from a Greek or Latin translation. The evidence shows it is an original Hebrew document. In the current Hebrew Matthew manuscripts, scholars are not saying that every single letter and word is what Matthew wrote in the first century. Matthew wrote 1300 years before Shim Tov. It was copied for many generations, and things could have changed. Things changed over the generations in the Greek. There are over 5,000 manuscripts in Greek, and no two are identical. The Greek is still the primary text of the New Testament. The Hebrew serves as another witness to the message Jesus taught. Some things that are lost in the Greek are preserved in the Hebrew. The more witnesses you have, the better.

Recently, Nehemiah Gordon and Keith Johnson, using 28 manuscripts of the Hebrew Matthew, started Hebrew Gospel Pearls, an in-depth study of the Hebrew Matthew.

The Writings of Josephus and Philo

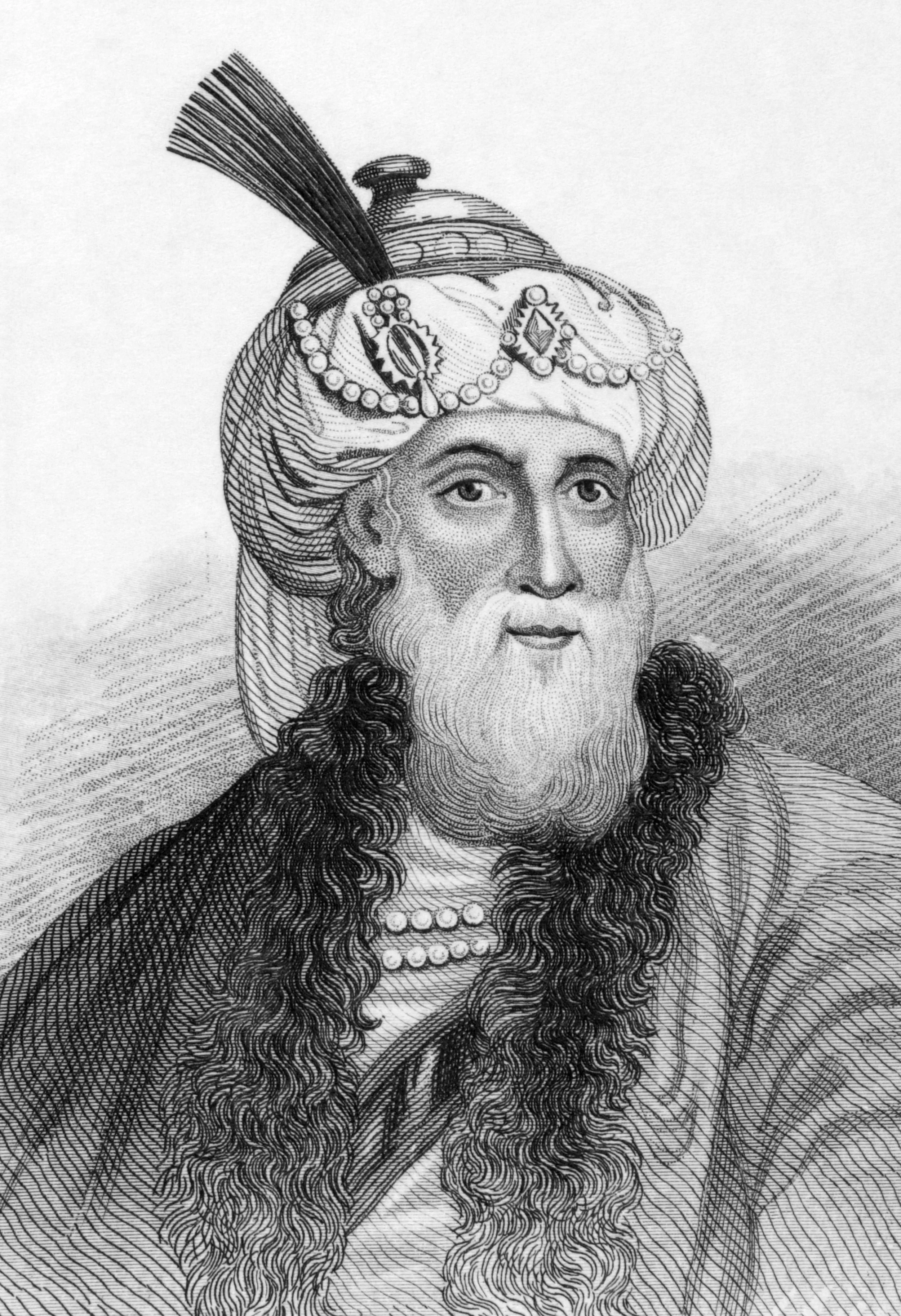

Flavius Josephus (c. 37 – c. 100 AD) was a Jewish historian, military commander, and statesman who lived during the first century of the Common Era. Born in Jerusalem to a priestly and aristocratic family, Josephus became a military leader during the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 AD). He initially fought against the Romans but later surrendered to General Vespasian after a siege. Josephus then became a prisoner of war and, over time, aligned himself with the Romans.

Josephus is best known for his historical works, particularly "The Jewish War" and "Jewish Antiquities." In "The Jewish War," he chronicles the events of the First Jewish-Roman War, providing a detailed account of the conflict and its aftermath. "Jewish Antiquities" covers a broader historical scope, offering a narrative of Jewish history from the world's creation to Josephus's time. He also wrote other works, such as "Against Apion" and "The Life of Flavius Josephus."

Josephus's writings are valuable for understanding Jewish history, the Jewish-Roman conflicts, and the social and political context of the time. However, scholars recognize that Josephus, having aligned himself with the Romans, may have presented events and characters in a way that favored his Roman patrons. Despite this potential bias, his works remain essential sources for studying the ancient Jewish world and the interactions between the Jews and the Roman Empire.

Titus Flavius Josephus

Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – c. 50 CE) was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, during the Second Temple. He is best known for his attempts to harmonize Greek philosophy, particularly the teachings of Plato and Stoicism, with Jewish religious thought. Philo's works bridge the gap between Hellenistic philosophy and Jewish theology, making him a significant figure in the history of Jewish philosophy.

Philo's philosophy revolves around believing that Greek philosophy and Jewish theology could be reconciled. He interpreted the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) allegorically to find philosophical truths, emphasizing biblical stories' allegorical and symbolic meanings. The prevailing Hellenistic intellectual currents profoundly influenced Philo's ideas, especially the Logos (Word) concept as a divine intermediary between God and the world.

One of Philo's key contributions is his development of the idea of the Logos. He identified the Logos with the intermediary between God and the material world, drawing parallels between this concept and the divine wisdom found in Proverbs. This notion of the Logos would later influence Christian theological developments, especially in understanding the nature of Christ.

Philo's surviving works include philosophical treatises, commentaries on the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible), and various essays. Notable works include "On the Creation," "On the Contemplative Life," and "Allegorical Interpretation."

While Philo's writings did not majorly impact mainstream Judaism during his time, they renewed interest in later centuries, especially among Christian theologians who found parallels between his ideas and Christian doctrines.

Development of Literature after the First Century

Only two sects of Judaism survived after the first century to produce and transmit any significant additions to Jewish literature: Pharisaic Judaism and the Nazarenes, i.e., the Jewish believers in Jesus. All subsequent Jewish literature results from Pharisaic Judaism and all New Testament literature results from followers of Jesus. The last canonized pieces of literature we possess from the Nazarenes include the Gospel of John, the Johannine epistles, and the book of Revelation, all written near the end of the first century. However, several apocryphal works should also be attributed to the early Jewish believers, such as the Didache, the Epistle of Clement, etc.

The second century came with a new generation of Jewish writers. Building on the work of Hillel, who had lived a century before him, Rabbi Yishmael ben Elisha codified a system of rules for interpreting the Torah. His thirteen principles of interpretation are still recited daily as part of the morning devotions before prayer. They can be found in any standard Siddur (Jewish prayer book).

From his exposition on the rules for interpreting Torah, we can learn about the methods and methodologies employed by the Tanna'im (teachers) when deducing a ruling from Scripture. Not surprisingly, many of the principles he lists can be identified as methods used by Jesus.

At the same time that Yishmael ben Elisha was codifying the rules of Torah study, Rabbi Akiva ben Yosef was making up new ones. Akiva invented new methods for expositing Scripture based upon interpreting every jot and tittle of the text.

Rabbi Akiva made the tragic mistake of designating the Jewish terrorist Bar Kosiva as Messiah and began the Second Jewish Revolt, also known as the Bar Kochba Revolt, occurring from 132 to 136 CE. The Jewish believers in Jesus could not endorse Bar Kochba as the Messiah, and they suffered under his cruel zealotry. At significant cost and embarrassment to Rome, Bar Kochba inflicted heavy damage on Roman Emporer Hadrian's legions. Rome martyred Akiva along with thousands of Jews. The briefly lived revolution resulted in a massive Roman persecution under Emperor Hadrian (who ruled from 117 CE to 138 CE) and the expulsion of all Jews from Jerusalem, which Hadrian rebuilt as the Roman city, Aelia Capitolina. The Talmud calls the Hadrianic Era the "Great Persecution."

In the early second century, Greek Christianity began producing apocryphal fiction detailing the infancy of Jesus, the acts of the apostles, the life of Mary, and so on. The Epistle of Barnabas, an Apostolic-era epistle redacted into a rant against Judaism, belongs to this period and the writings of the Apostolic Fathers. Early church literature is far removed from the Jewish roots of the Christian faith.

The second-century church saw the rise of Marcion the Heretic (born around 85 CE and died around 160 CE), who attempted to erase all Jewish elements from Christianity and remove the Old Testament from the Christian literature. Marcion was part of the Gnostic movement, an esoteric form of Christianity that rejected the God of the Jews as an evil, lesser being and rejected his creation (the material world) as the antithesis of the actual spiritual world.

Gnostic Christians began to produce their own gospels, such as the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Philip, the Gospel of Truth, and the Gospel of Judas. Credible scholars agree that the Gnostic gospels, except for the Gospel of Thomas, have no connection to historical traditions about Jesus of Nazareth.

The Mishnah

Emporer Hadrian's persecution damaged the oral transmission process. After two disastrous wars with Rome, widespread dispersion, and constant persecution, the Jewish sages realized that the teacher-disciple transmission process, instituted originally by the Great Assembly, was falling apart. One of Rabbi Akiva's disciples, the famous Rabbi Meir, began committing the gigantic body of oral tradition to writing.

His work was continued by a wealthy and prominent, distant relative of Jesus and descendant of Hillel named Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi (Judah the Prince). Judah the Prince completed what Meir had begun. The finished work was a meaningful, skeleton-like, written version of litigious legal material called the Mishnah. Mishnah means "repetition." because before being committed to writing, the material had been passed from generation to generation through memorization by repetition.

Judaism refers to the Mishnah as the Oral Torah. Rabbi Yehudah completed the work around 200 CE, immediately becoming the Torah study textbook for Jews.

The Gemara

The sages who lived after the compilation of the Mishnah are called Amora'im (the Savers). They began studying and arguing over the Mishnah in their various schools and academies in Babylon and Israel.

In their arguments and discussions over the Mishnah, the Amora'im told and retold the oral traditions that they had received from their masters.

They often found those traditions to be at odds with the rulings recorded in the Mishnah, resulting in more argumentation to reconcile the contradictions and find proof in Scripture. In the process, they discussed old parables, amusing anecdotes, pieces of oral law, rabbinic sayings, customs, midrashim, folklore, and superstition, all of which the study hall scribes recorded. The rabbis eventually combined those study-hall notes as a commentary on the Mishnah. The commentary is called Gemara (X712), which means "the completion" because it adds the oral traditions, proof texts, and arguments that the Mishnah left out. In that sense, it completes the Mishnah.

Writings of Eusebius

While the Amora'im produced Gemara, the Roman Empire converted to Christianity under Emperor Constantine. Constantine contracted a bishop from Caesarea named Eusebius to write a history of Christianity.

Eusebius had an extensive library of early Christian writings, many dating back to the beginning of the first century. He used these and the text of Josephus as his primary sources for writing out his indispensable Ecclesiastical History. Less than reliable, it remains our best source of authentic, extra-biblical information about early Christianity.

The Talmud

Two prominent schools of Amora'im, one in Galilee and one in Babylon, independently produced written Gemara on the Mishnah. In the fourth and fifth centuries, the academies in Galilee compiled their Gemara with the Mishnah to form the Talmud Yerushalmi collection (Jerusalem Talmud). The Babylonian academies compiled their Gemara with the Mishnah to form an even more extensive and copious collection called the Talmud Bavli (Babylonian Talmud). Talmud means "study." The Talmud results from nine hundred consecutive years of Bible study in both versions.

Midrash Rabbah

While the sages edited the Gemara into the Talmuds, they collected the vast body of midrash into various collections. The primary collection, which has survived the ages, is the Midrash Rabbah. Some of the material was not recorded until the Middle Ages. Still, the vast majority belongs to the Amora'im age and reflects those generations' ideas and concerns. However, the legends, folklore, and traditions transmitted in the midrash are far older and often date back to the Apostolic Era. Various midrash collections continued to be compiled and transmitted throughout the Middle Ages, primarily drawing on older collections and traditions.

Rashi and Rambam

The eleventh century saw the beginning of the Crusades and a new era of hostility between Christianity and Judaism. It also saw the rise of Judaism's most famous commentator on Torah and Talmud, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchak.

His prolific commentaries on the Bible and the Talmud became instant classics and the standard for Jewish Torah study. He is best known by the acronym of his name, RASHI.

By the time Rashi wrote. Jewish literature had become so vast and sprawling that only the highly educated could make heads or tails of it. In the mid-twelfth century, Rabbi Moses ben Maimon set out to organize Jewish law.

He is also known by his acronym RAMBAM, or simply as Maimonides. In addition to his comprehensive code of Jewish law, Mishneh Torah, and codification of the 613 commandments of the Torah, he authored several other works now considered staples of Jewish studies, including the famous Ani Ma'amin (I Believe), which is the Thirteen Fundamentals of Jewish belief and has served as a creed for normative Judaism ever since.

Kabbalah

In the thirteenth century, the mystical work entitled Zohar appeared. Zohar means "resplendence." The purported author claimed to have discovered a long-lost set of manuscripts by the mystical second-century Tanna Shimon ben Yochai. Serious scholars dismiss the claim but admit that the Zohar contains a digest of earlier Jewish traditions, interpretations, and mysterious trends. It is undoubtedly an accurate reflection of early Medieval Jewish Mysticism, a field of theology often wrongly identified with hocus-pocus and occultism. Mysticism is the study of the mystical, the unseen ways in which God runs the universe and reveals Himself to the world. For example, the prelude to the Gospel of John is a classic example of first-century mysticism.

The books of the Zohar and the contemporary literature they spawned are collectively called the Kabbalah, which means "received." By the time of the Protestant Reformation, Protestant and Catholic scholars had begun digging into Kabbalah. They found therein many impressive affinities with the apostolic teachings and theology. Spurred by such exciting discoveries, the Pope ordered a version of the Zohar translated into Latin.

Kabbalistic literature is not intended literally. It is highly symbolic, and even Judaism warns the layman to stay away from those mystical works because they will be inevitably misunderstood and misused.