11) Extra-Biblical Literature - Part 1

Introduction to Extra-Biblical Literature

Throughout the site, I will utilize several extra-biblical sources to provide the framework to better understand Jewish thought and specifically Second Temple-era Judaism. While we will primarily rely on the Bible and its Old and New Testaments, we will sometimes pull from extra-biblical sources to help define terms within the Bible that have not been clearly defined. For example, in Matthew, when John the Baptist and Jesus appear on the scene, they talk about the kingdom of heaven and the Gospel. What did those terms mean to Jews in the first century? Years later, when Paul wrote "works of the law," what did he mean by that? He never officially defined what he meant in his writings, implying a pre-existing audience understanding.

Though we may know what the Bible says, we cannot always know what specific phrases or words mean. We can only appreciate the work's depth, meaning, and message when we can determine the author's methods and objectives. Another way of understanding the author is realizing the writing's language, history, and context. The best way to do this is to compare it to similar literature and find its place in the history and culture that generated it.

When comparing Biblical literature to extra-biblical literature, we will maintain the Bible itself is divinely inspired. Therefore, the Bible will be given a higher priority when compared to other similar literature. However, these additional sources can be helpful in our understanding of the Bible and Jewish thought.

We can learn a great deal from Jewish rabbis. We must recognize that the Jewish people have the God-given authority to interpret and apply the Scriptures.

They are Israelites, and to them belong the adoption, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the worship, and the promises. (Romans 9:4, ESV Bible)

Then what advantage has the Jew? Or what is the value of circumcision? Much in every way. To begin with, the Jews were entrusted with the oracles of God. (Romans 3.1-2, ESV Bible)

The LORD Himself gave the Jewish community the authority to interpret the Scriptures (Deuteronomy 17:6-13), and Jesus endorsed that authority (Matthew 23:1-3):

On the evidence of two witnesses or of three witnesses the one who is to die shall be put to death; a person shall not be put to death on the evidence of one witness. The hand of the witnesses shall be first against him to put him to death, and afterward the hand of all the people. So you shall purge the evil from your midst. “If any case arises requiring decision between one kind of homicide and another, one kind of legal right and another, or one kind of assault and another, any case within your towns that is too difficult for you, then you shall arise and go up to the place that the LORD your God will choose. And you shall come to the Levitical priests and to the judge who is in office in those days, and you shall consult them, and they shall declare to you the decision. Then you shall do according to what they declare to you from that place that the LORD will choose. And you shall be careful to do according to all that they direct you. According to the instructions that they give you, and according to the decision which they pronounce to you, you shall do. You shall not turn aside from the verdict that they declare to you, either to the right hand or to the left. The man who acts presumptuously by not obeying the priest who stands to minister there before the LORD your God, or the judge, that man shall die. So you shall purge the evil from Israel. And all the people shall hear and fear and not act presumptuously again. (Deuteronomy 17:6-13, ESV Bible)

Then Jesus said to the crowds and to his disciples, “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, so do and observe whatever they tell you, but not the works they do. For they preach, but do not practice. (Matthew 23:1-3, ESV Bible)

For those of you who would like more information on these extra-biblical sources, I will encourage you to keep reading this post and the next post, Part 2.

Second Temple Model of Ancient Jerusalem

The Establishment of Second Temple Literature

The Edict of Cyrus, allowing the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild the temple, is traditionally dated around 538 BCE. This date is based on historical and biblical accounts, including the books of Ezra and 2 Chronicles. The precise year might vary slightly in different sources, but it generally falls within the late 6th century BCE. Cyrus's decision to allow the Jews to return and rebuild the temple was likely influenced by religious tolerance, humanitarian motives, political considerations, and possibly the fulfillment of perceived prophecies. The construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem began under the leadership of Zerubbabel, a governor appointed by the Persian king Cyrus. The Second Temple in Jerusalem began around 537 BCE and was completed in 516 BCE.

Ezra, a priest and scribe, returned from Babylon to Jerusalem in the 5th century BCE (458 BCE) during the rule of the Persian Empire. His return is associated with the reign of King Artaxerxes I. His return aimed to lead a group of Jewish exiles back to Jerusalem and promote religious and legal reforms.

Ezra's mission included enforcing the observance of the Mosaic Law and addressing issues among the Jewish community, such as intermarriage with non-Jews. He played a crucial role in teaching and reestablishing proper worship practices, ensuring that the people followed the laws outlined in the Torah.

The biblical book of Ezra provides an account of his efforts, detailing the challenges faced by the returning exiles and the steps taken to rebuild and reform the Jewish community in Jerusalem after the Babylonian exile.

Ezra played a vital role in the religious and legal reforms associated with establishing the Great Assembly. The Great Assembly is a legendary body of 120 members, including prophets and scholars, who shaped Jewish religious practices and preserved the sacred texts.

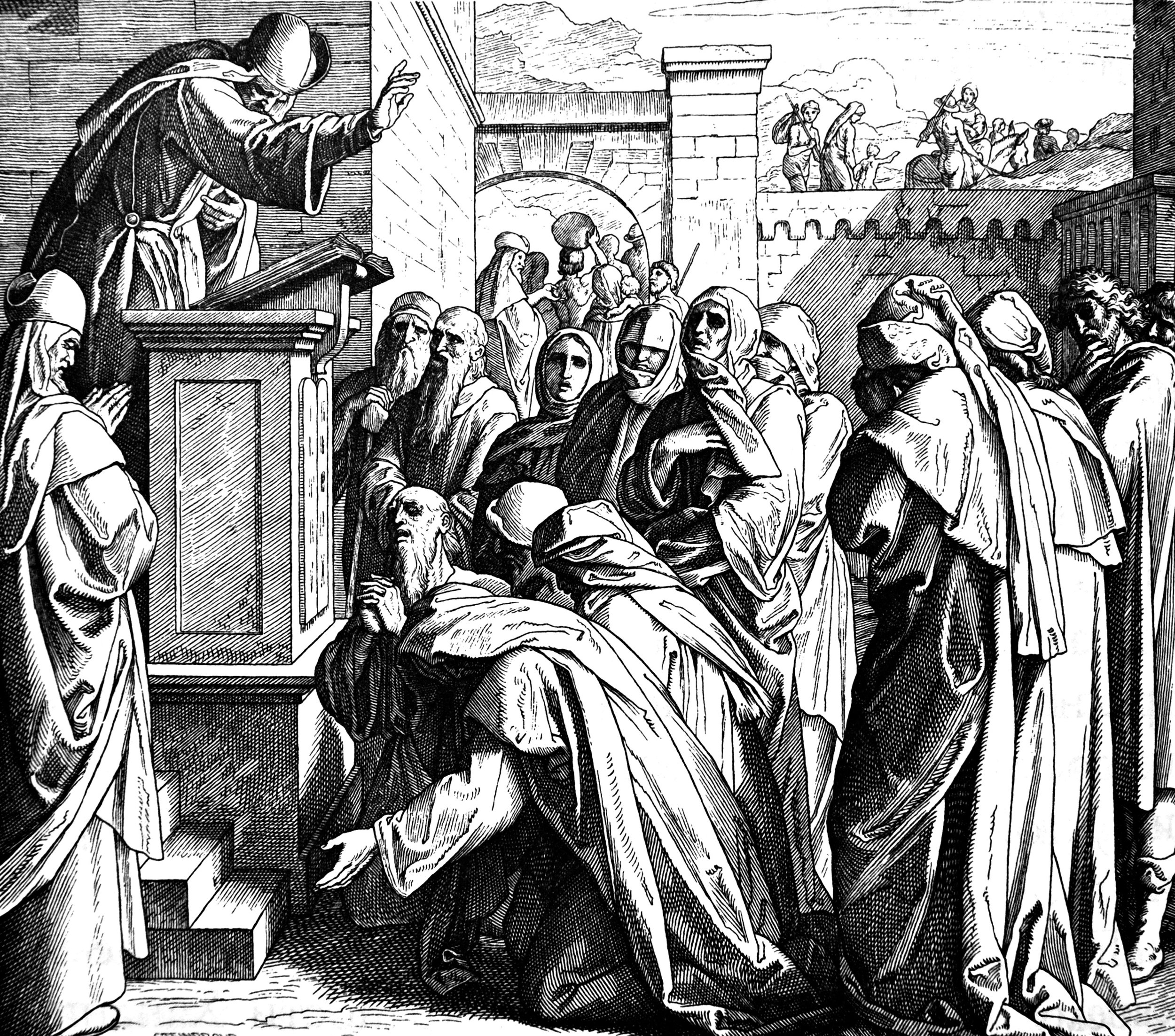

Ezra reads the book of the Law

To summarize, the Second Temple's construction began under Zerubbabel, and Ezra's return occurred during the period when the temple was already standing, with Nehemiah contributing to the broader restoration efforts in Jerusalem, playing a significant role in the later stages of the construction of the city walls.

The Great Assembly and Second Temple Literature

During the Second Temple period, which spans from the construction of the Second Temple in 516 BCE to its destruction in 70 CE, there was a notable flourishing of Jewish literary activity. This period saw the composition of various texts now collectively known as intertestamental or Second Temple literature. These writings were produced between the close of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the emergence of the Apostolic writings (New Testament).

The Great Assembly contributed significantly to this era's intellectual and spiritual climate. The Great Assembly significantly influenced the development of intertestamental Jewish literature. The Great Assembly is credited with finalizing the canonization of the Hebrew Scriptures (Tanakh or Old Testament). They played a role in preserving and transmitting the sacred texts that formed the foundation for later Jewish writings. The assembly was involved in transmitting oral traditions, interpretations, and teachings. This oral tradition and the written Scriptures became the basis for various literary works in the intertestamental period. The Great Assembly is associated with the codification of Jewish law, known as the Mishnah. This legal compilation became a cornerstone for later Rabbinic Judaism. It influenced ethical and moral teachings in works like the Wisdom of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) and the Wisdom of Solomon.

The intertestamental period witnessed the emergence of apocalyptic literature, marked by visionary and symbolic writings that often explored themes of eschatology. While the Great Assembly may not have directly produced apocalyptic texts, its influence on Jewish thought contributed to the ideological backdrop for later apocalyptic works.

Some texts attributed to figures from the past, known as Pseudepigrapha, were composed during this period. While not directly linked to the Great Assembly, these writings reflect Jewish thinkers' creative and interpretative spirit grappling with theological and historical questions.

The Great Assembly's impact on the canonization of Scripture, the development of legal traditions, and the transmission of oral teachings provided a fertile ground for the growth of intertestamental Jewish literature. The intellectual and religious legacy of the Great Assembly laid the groundwork for the diverse literary expressions that emerged during this transformative period in Jewish history.

Summary

This post delves into the intricate tapestry of biblical and extra-biblical sources, navigating through the Edict of Cyrus and Ezra's return to elucidate the multifaceted landscape of Jewish thought. Focusing on the Great Assembly, we looked at how it unveils its pivotal role in canonization, legal traditions, and the flourishing of intertestamental Jewish literature. This literary outpouring, influenced by the Assembly's ethical teachings, laid a profound foundation, fostering diverse expressions that characterized the transformative period of the Second Temple era.

The following post, titled "Extra-Biblical Literature - Part 2: A Brief Overview of Extra-Biblical Sources," will be optional study material. Throughout the site, I will frequently pull from sources other than the Bible, and the next post will be a great resource if you want to learn more about these writings.